“I often fought, sometimes I was beaten, but I have never been killed off.”

—General François-Athanase de Charette, leader of the Vendée revolt

Amidst the bloody horror of the French Revolution, stories of heroism miraculously arose.

One of the most famous is the tragic but glorious tale of the rebels of the Vendée—a region in western France that was devoutly Catholic and resisted the vicious attacks on the Church enacted by the revolutionary government.

The Vendéans weren’t initially against all the Revolution’s aims, but things got ugly when the Civil Constitution of the Clergy was passed in the summer of 1790. This decree abolished over a third of dioceses and a quarter of the parishes in France. Clergy were exiled, interned, and killed for refusing to swear a required oath of loyalty to the state. The decimation of the Catholic religion was clearly underway, and the Vendéans would not stand for it.

The tipping point came when the government introduced conscription. The Vendéans had no interest in fighting for the Republic, and they instead organized themselves into the Catholic and Royal Army. It was composed mostly of peasants, in the name of whom the Revolution—ironically—claimed to act.

Members of the Catholic nobility joined later, bringing much-needed military expertise with them. Some of the revolt’s most famous leaders were these young aristocrats—men mostly in their 20s and 30s—who would lay down their lives on the battlefield or by execution.

The Catholic and Royal Army had some success initially, taking several towns and the city of Angers by midsummer 1793. But in autumn, the Revolutionary Army had reinforced and reorganized themselves to deadly effect. They crushed the rebels at the Battle of Le Mans, and engaged in dreadful slaughter of prisoners afterwards.

The terror had only just begun. In November, a law came into effect that delineated a plan to exterminate the Vendéans—including women, children, and the elderly. The groundwork for the plan had been laid even earlier, in the spring of that year.

At the end of November, the inhuman General Louis Marie Turreau took command of the Republican army and formed “infernal columns” that marched through the Vendée, burning villages and slaughtering the inhabitants.

Though the rebels were effectively defeated at the Battle of Savenay in December 21, 1793, the terror against civilians lasted from August 1793 through July 1794, a campaign that has been accurately called genocide.

With the recall of Turreau and the rise of a more moderate faction in the government, an amnesty was reached at the end of 1794. Early the next year, the rebels were granted freedom of worship and exemption from conscription. When Napoleon—a great admirer of the Vendéans—came to power, he further granted compensation and assistance to the devastated region.

The Republic tried to bury the history of this rebellion, and for a long time the official narrative excluded much mention of it. Even up until the 20th century the story was not fully known. A French historian, Reynald Secher—whose ancestors died in the Vendée—decided to change that. Beginning in the 1970s and continuing for decades, his monumentally-important research shed new light on this period of history.

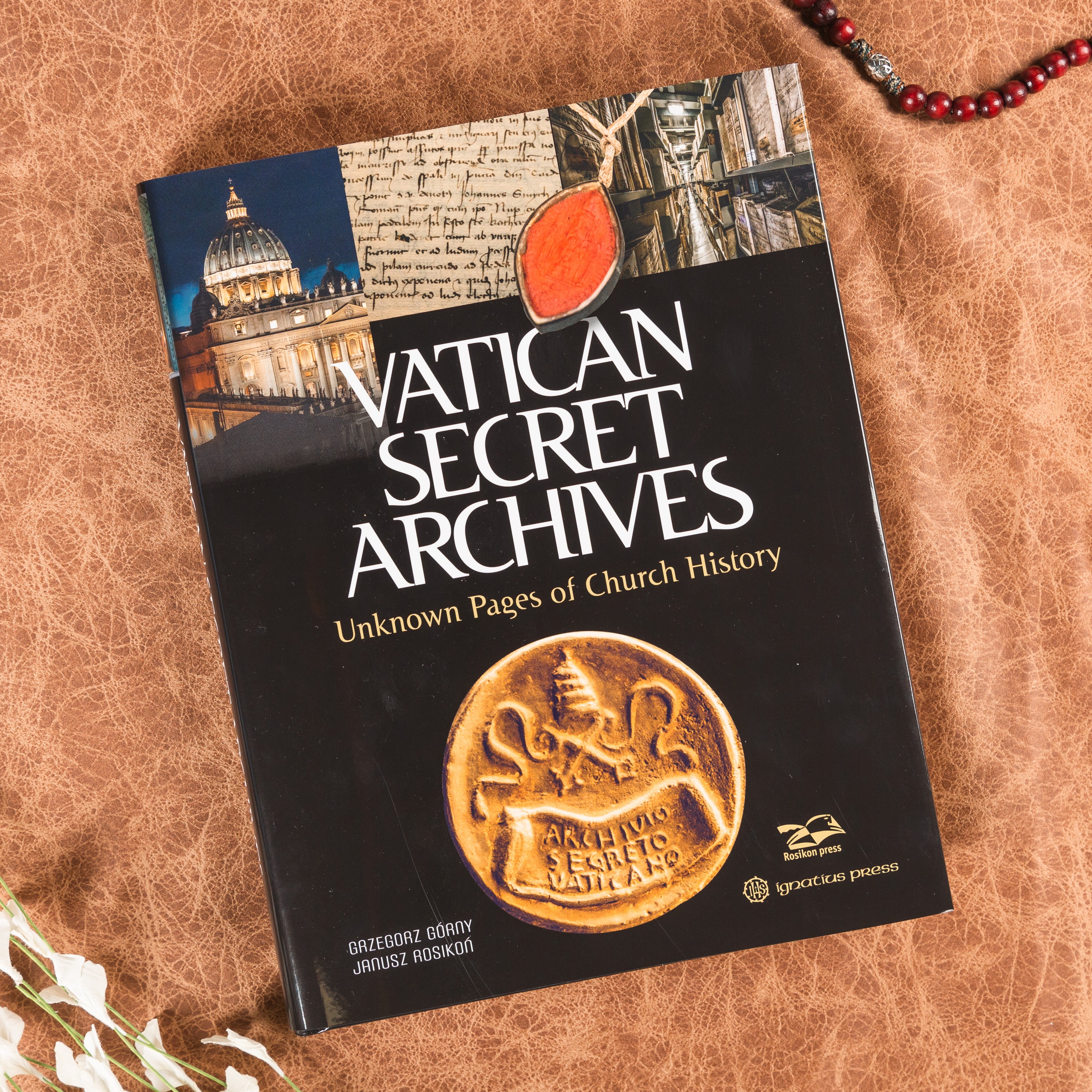

You can dig into this amazing research in Vatican Secret Archives—The Unknown Pages of Church History. This captivating book dedicates an entire chapter to the French Revolution and the Vendée, using Secher’s research as a primary source. Other chapters explore equally fascinating topics: what really happened at Galileo’s trial, the role of the Vatican in World War II, the real story of the missionaries in the New World, and so much more. Available today at The Catholic Company!