“Have you lost your mind?”

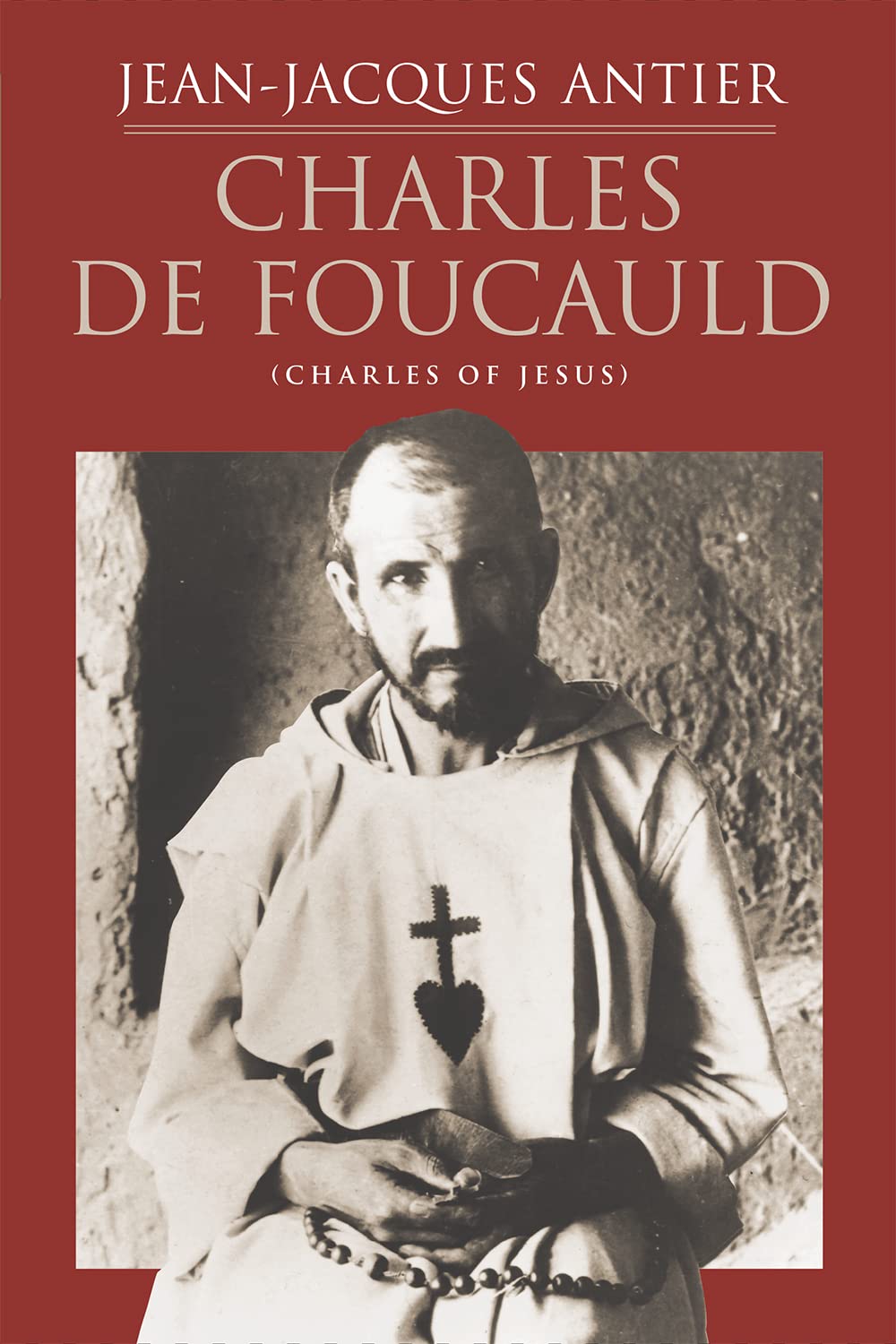

Charles must have heard this a few times as he prepared to dive into the uncharted landscape of Morocco, where few Europeans had officially gone. No one dared. It was off-limits to them, home only to Muslims and Jews, and any outsider brazen enough to cross its borders was likely to wind up dead.

But such things were hardly a hindrance to this unusual character.

Behind him lay a life of profligacy that he had lived as a less-than-model French military officer, after drifting away from the Faith of his childhood; before him lay a future filled with the unknown. He had found himself restless with ordinary military life and found his stride in the deployments to French Africa, so here, at the entrance to Morocco, at the yawning mouth of death and danger, was where he wanted to be.

But no turning of his still-boyish imagination could have prepared him for what the future really held, and how much the desert—which had captured his heart so well—would capture it still more.

He survived the Morocco adventure by hiring a Jewish guide and disguising himself as a rabbi. Those who suspected him to be a Christian kept his secret. Beneath the folds of his robes, he jotted down surreptitious notes on his surroundings—charting territory unknown to most of his ilk.

Returning to France, grace began to move his heart. He felt an emptiness and longing that even another trip across the Sahara did not fill. His cousin Marie, whose Catholic faith Charles had always admired if not imitated, advised him to visit a priest, Fr. Huvelin. After Charles found him in the confessional, the good priest ordered him to kneel and confess his sins. Charles obeyed, and then followed another immediate order to go receive Holy Communion.

And just like that, Charles was back from the dead. He would say afterwards:

“The moment I realized that God existed, I knew that I could not do otherwise than to live for him alone.”

The rest of his life would indeed be spent in continual striving for perfect imitation of Christ. He joined the Trappists in France, then—always called back to the desert—in Syria. Here he began to experience a profound inner peace, but in his heart there was still a striving to be more perfectly like Jesus, to pursue more poverty and solitude, and to found an order of his own.

His paths led him to Rome, to a gardener’s life in Nazareth, to priestly ordination in France, and finally back to Algeria, among the Tuareg people. Though he had written a rule for his order and hoped for companions to join him, no one did. But he was not discouraged.

Totally abandoned to the will of God, he faithfully lived the Beatitudes in his humble hermitage, spending endless hours in Adoration before the Blessed Sacrament and in service to those around him. He learned the Tuareg language, translated the Gospels and many Psalms into Tuareg, and wrote dictionaries and Tuareg poetry. He made few converts, but everyone knew he was a man of God.

When World War I broke out, Fr. de Foucauld built a fort to protect the people of the area. But marauders would invade the place and kill this saint of the Sahara, who—through so many toils and dangers—had become so much like Christ.

Charles was beatified in 2005 and canonized just this month, on May 15th. After his death, his order would finally spring into life: the Little Brothers and Sisters of Jesus.

This was just a quick summary of the captivating story of this incredible saint. Read more in his fascinating biography, Charles de Foucauld, by author Jean-Jacques Antier—available today at The Catholic Company!